I expect this module to stretch your mind and make you understand functions a little better. I don't expect you to suddenly master recursion.

We know that functions can call other functions inside their body, like:

let pi = 3.14

let findArea = (diameter) => diameter * diameter / 4 * pi

let findAreaOfSliceFromDiameter = (diameter) => findArea(diameter) / 8

findAreaOfSliceFromDiameter(14)In the above example we find the area of a slice of pizza based on the diameter of the pizza. Each slice of a 14" pizza holds roughly 19 square inches of pizza. We discover this by defining a function findArea that we call from findAreaOfSliceFromDiameter with the diameter parameter.

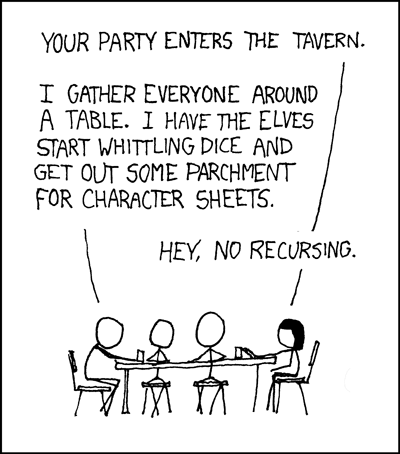

Recursion isn't a new kind of syntax, it's just the idea that a function can call itself over and over again, until it finds the answer we want it to.

We do this because often we're not smart enough to solve a problem with a single expression, and because it allows us to apply a set of rules to a problem over and over again, slightly modified each time, until the problem is solved.

We can use recursion to iterate through our expression again and again, for example:

// compound interest calculator

// calculate compounded interest over time

let calc = (rate, sum, time) => time > 0 ? calc(rate, sum + sum * rate, time - 1) : sumThat function was a mouthful, so lets split it into a few lines

// we split the expression in the function's body over three lines.

calc = (rate, sum, time) => time > 0 ? // is time greater than 0?

calc(rate, sum + sum * rate, time - 1) : // if yes, then recurse,

sum // otherwise, return the sum.So what's happening?

We declare calc with three parameters, the interest rate for a period (rate), the starting sum (sum), and the number of periods to compound (time). We check if time is zero, and if it is we return the sum we have calculated thus far. If time is greater then zero, we iterate again, adding the interest to the sum, and reducing the time left by 1.

Let us assume that a single pair of rabbits, in the wild, can produce 25 breeding pairs of rabbits in a single year (even with high mortality, old age, and predation). We want to figure out how many pairs of rabbits there are after X years.

That seems like a lot of stuff to pack into one function. Good thing we can actually write functions with statements inside of them!

let rabbitCalc = (years, pairs=1) => {

// function body

}We just introduced a couple new things here:

-

pairs=1: We defined a function parameter called pairs, but we said that it equals 1. We've given the second parameter of our function a default value of1. So now we can callrabbitCalc(10), and it will be like callingrabbitCalc(10, 1), but we can override the default value by callingrabbitCalc(10, 2)so now pairs is2instead of the default1. -

We used these things { } to define the body of our function. Now our function does whatever we tell it to between those curly brackets. We can write multiple statements, and when we're ready for our function to return a value, we just use the key word,

return.

Here's how to use that fancy new function body with a return statement.

let rabbitCalc = (years, pairs=1) => {

let nextGeneration = pairs * 25

return nextGeneration

}OK, so we're just calculating a single generation of rabbits right now. Let's add the recursion part.

let rabbitCalc = (years, pairs=1) => {

let generation = pairs * 25

return years > 1 ?

rabbitCalc(years - 1, generation) :

generation

}There's still something that's a bit hard to understand here:

return years > 1 ?

rabbitCalc(years - 1, generation) :

generationLet's introduce another kind of statement called if.

let rabbitCalc = (years, pairs=1) => {

if (years < 1) {

return pairs

}

return rabbitCalc(years - 1, pairs * 25)

}A couple things to understand here:

-

The if statement uses curly brackets again to execute everything in its body { } if the boolean in the parentheses ( ) is true.

-

returnonly happens once per function call, so if the return statement inside the if statement executes, then the function is over, and it never looks for the 2nd return statement below.

if (years < 1) {

return pairs

}if (boolean) {

body

}

Recursion is awesome. In the interest of learning we've picked examples that focus on numbers because we know how to do math in JavaScript, but where recursion is really helpful is in allowing us to iterate over nested data structures, something we will do during our course. It's definitely worth being exposed to.

We've also learned to use if statements, and functions with return statements. These are powerful tools. Keeping everything in a single expression makes it easier to write code without bugs (mistakes), but it also makes it harder to read and write longer functions.

// positive powers

let toPowerOf = (num, power) => power > 0 ?

toPowerOf(num * 10, power - 1) :

num

// FYI you can just do power like this:

1e5 // one to the power of five// factorial

let fact = (n) => n > 1 ? n * fact(n - 1) : 1// compute dimensions

let dims = (number, dimensions, value=number) => {

if (dimensions === 0) {

return 0

}

if (dimensions === 1) {

return value

}

return dims(number, dimensions - 1, value * number)

}

// FYI you can just do dimensions like this:

2**2 // two squaredOh hey, this one isn't recursive at all, because you need a break:

let findAreaOfSliceFromDiameter = (diameter) => {

let pi = 3.14

let findArea = (d) => d * d / 4 * pi

return findArea(diameter) / 8

}Study that last one, it's not recursive, but does it make sense to you? We nested a function declaration inside another function, neat huh? How about the names of the parameters in the nested function? Does that clarify the way that parameters work?

-

Rewrite this:

let calc = (rate, sum, time) => time > 0 ? calc(rate, sum + sum * rate, time - 1) : sum

As a multi-statement function, with if statements instead of a ternary operator (boolean ? then : else).

-

Rewrite all the functions you have previously seen and written in our other homework using the new syntax.

For example:

let f = (x) => x + 1

becomes:

let f = (x) => { return x + 1 }

-

Think up your own recursive function. It doesn't have to be amazing. Write it in any syntax you like.