Flash storage, also called solid state, has multiple advantages over rotating storage. First, the absence of mechanical and moving parts eliminate noise, increase reliability and resistance to shock and vibrations, and also reduces heat dissipation as well as power consumption. Second, random access to data is also much faster, as you no longer have to move a disk head to the right location on the medium, which can take milliseconds.

Flash also has its shortcomings, of course. First, for the same price, you have about 10 times less solid state storage than rotating storage. This can be an issue with operating systems that require Gigabytes of disk space. Fortunately, Linux only needs a few MB of storage. Second, writing to flash storage has special constraints. You cannot write to the same location on a flash block multiple times without erasing the entire block, called an “erase block”. This constraint can also cause write speed to be much lower than read speed. Third, flash blocks can only withstand a rather limited number of erases (from a few thousand for today densest NAND flash to one million at best). This requires to implement hardware or software solutions, called “wear leveling”, to make sure that no flash block gets written to much too often that the others

NOR flash was the first type of flash storage that was invented. NOR is very convenient as it allows the CPU to access each byte one by one, in random order. This way, the CPU can execute code directly from NOR flash. This is very convenient for bootloaders, which do not have to be copied to RAM before executing their code.

The NOR flash architecture provides enough address lines to map the entire memory range. This gives the advantage of random access and short read times, which makes it ideal for code execution. Another advantage is 100% known good bits for the life of the part. Disadvantages include larger cell size resulting in a higher cost per bit and slower write and erase speeds.

In NOR gate flash, each cell has one end connected directly to ground, and the other end connected directly to a bit line. This arrangement is called "NOR flash" because it acts like a NOR gate: when one of the word lines (connected to the cell's Control Gate) is brought high, the corresponding storage transistor acts to pull the output bit line low.

NAND flash is today’s most popular type of flash storage, as it offers more storage capacity for a much lower cost. The drawback is that NAND storage is on an external device, like rotating storage. You have to use a controller to access device data, and the CPU cannot execute code from NAND without copying the code to RAM first. Another constraint is that NAND flash devices can come out of the factory with faulty blocks, requiring hardware or software solutions to identify and discard bad blocks.

NAND flash, in contrast, has a much smaller cell size and much higher write and erase speeds compared to NOR Flash. Disadvantages include the slower read speed and an I/O mapped type or indirect interface, which is more complicated and does not allow random access. It is important to note that code execution from NAND Flash is achieved by shadowing the contents to a RAM, which is different than code execution directly from NOR Flash. Another major disadvantage is the presence of bad blocks. NAND Flash typically have 98% good bits when shipped with additional bit failure over the life of the part, thus requiring the need for error correcting code (ECC) functionality within the device.

NAND flash also uses floating-gate transistors, but they are connected in a way that resembles a NAND gate: several transistors are connected in series, and only if all word lines are pulled high (above the transistors' VT) is the bit line pulled low.

The first type of Nand Flash emulates a standard block interface, and contains a hardware “Flash Translation Layer” that takes care of erasing blocks, implementing wear leveling and managing bad blocks. This corresponds to USB flash drives, media cards, embedded MMC (eMMC) and Solid State Disks (SSD). The operating system has no control on the way flash sectors are managed, because it only sees an emulated block device. This is useful to reduce software complexity on the OS side. However, hardware makers usually keep their Flash Translation Layer algorithms secret. This leaves no way for system developers to verify and tune these algorithms, and I heard multiple voices in the Free Software community suspecting that these trade secrets were a way to hide poor implementations. For example, I was told that some flash media implemented wear leveling on 16 MB sectors, instead of using the whole storage space. This can make it very easy to break a flash device.

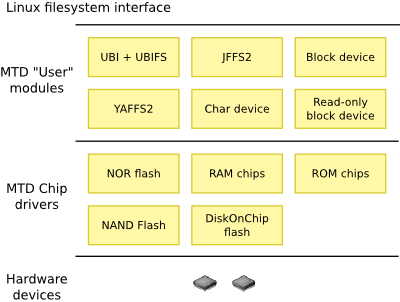

The second type of Nand Flash is raw flash. The operating system has access to the flash controller, and can directly manage flash blocks. Counting the number of times a block has been erased is also possible (“block erase count”). The Linux kernel implements a Memory Technology Device (MTD) subsystem that allows to access and control the various types of flash devices with a common interface. This gives the freedom to implement hardware independent software to manage flash storage, in particular filesystems. Freedom and independence is something we have learned to care about in our community.

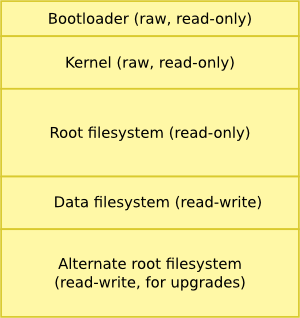

MTD devices are usually partitioned. This is useful to define areas for different purposes. Raw means that no filesystem is used. This is not needed when you just have one binary to store, instead of multiple files.

What’s special in MTD partitions is that there is no partition table as in block devices. This is probably because flash is an unsafe location to store such critical system information, as flash blocks may become bad during system life.

Instead, partitions are defined in the kernel. An example is found in the arch/arm/mach-omap2/board-omap3beagle.c file in the kernel sources, defining flash partitions for the Beagle board:

static struct mtd_partition omap3beagle_nand_partitions[] = {

/* All the partition sizes are listed in terms of NAND block size */

{

.name = "X-Loader",

.offset = 0,

.size = 4 * NAND_BLOCK_SIZE,

.mask_flags = MTD_WRITEABLE, /* force read-only */

},

{

.name = "U-Boot",

.offset = MTDPART_OFS_APPEND, /* Offset = 0x80000 */

.size = 15 * NAND_BLOCK_SIZE,

.mask_flags = MTD_WRITEABLE, /* force read-only */

},

{

.name = "U-Boot Env",

.offset = MTDPART_OFS_APPEND, /* Offset = 0x260000 */

.size = 1 * NAND_BLOCK_SIZE,

},

{

.name = "Kernel",

.offset = MTDPART_OFS_APPEND, /* Offset = 0x280000 */

.size = 32 * NAND_BLOCK_SIZE,

},

{

.name = "File System",

.offset = MTDPART_OFS_APPEND, /* Offset = 0x680000 */

.size = MTDPART_SIZ_FULL,

},

};You can override these default definitions without having to modify the kernel sources.You first need to find the name of the MTD device to partition, as you may have multiple ones. Look at the kernel log at boot time. In the Beagle board example, the MTD device name is omap2-nand.0:

omap2-nand driver initializing

ONFI flash detected

NAND device: Manufacturer ID: 0x2c, Chip ID: 0xba (Micron NAND 256MiB 1,8V 16-bit)

Creating 5 MTD partitions on "omap2-nand.0":

0x000000000000-0x000000080000 : "X-Loader"

0x000000080000-0x000000260000 : "U-Boot"

0x000000260000-0x000000280000 : "U-Boot Env"

0x000000280000-0x000000680000 : "Kernel"

0x000000680000-0x000010000000 : "File System"The Linux kernel offers an mtdpartss boot parameter to define your own partition boundaries. We have just defined 6 partitions in the omap2-nand.0 device.

mtdparts=omap2-nand.0:128k(X-Loader)ro,256k(U-Boot)ro,128k(Environment),4m(Kernel)ro,32m(RootFS)ro,-(Data)Note that partition sizes must be a multiple of the erase block size. The erase block size can be found in /sys/class/mtd/mtdx/erasesize on the target system.

- First stage bootloader (128 KiB, read-only)

- U-Boot (256 KiB, read-only)

- U-Boot environment (128 KiB)

- Kernel (4 MiB, read-only)

- Root filesystem (16 MiB, read-only)

- Data (remaining space)

Now that partitions are defined, you can display the corresponding MTD devices by viewing /proc/mtd (the sizes are in hexadecimal):

dev: size erasesize name

mtd0: 00020000 00020000 "X-Loader"

mtd1: 00040000 00020000 "U-Boot"

mtd2: 00020000 00020000 "Environment"

mtd3: 00400000 00020000 "Kernel"

mtd4: 02000000 00020000 "File System"

mtd5: 0dbc0000 00020000 "Data"You can access MTD device number X through two types of interfaces.

The first interface is a /dev/mtdX character device, managed by the mtdchar driver. In particular, this character device provides ioctl commands that are typically used by mtd-utils commands to manipulate and erase blocks in an MTD device.

The second interface is a /dev/mtdblockX block device, handled by the mtdblock driver. This device is mostly used to mount MTD filesystems, such as JFFS2 and YAFFS2, because the mount command primarily works with block devices.

These commands are available through the mtd-utils package in GNU/Linux distributions and can also be cross-compiled from source by embedded Linux build systems such as Buildroot and OpenEmbedded. Simple implementations of the most common commands are also available in BusyBox, making them much easier to cross-compile for simple embedded systems.

The clean way to manipulate MTD devices is through the character interface, and using the mtd-utils commands. Here are the most common ones:

- mtdinfo: get detailed information about an MTD device

- flash_eraseall: completely erase a given MTD device

- flashcp: write to NOR flash

- nandwrite: write to NAND flash

- mkfs.jffs2, mkfs.ubifs: Flash filesystem image creation tools:

- UBI utilities

Journaling Flash File System version 2 (JFFS2), added to the Linux kernel in 2001, is a very popular filesystem for flash storage. As expected in a flash filesystem, it implements bad block detection and management, as well as wear leveling. It is also designed to stay in a consistent state after abrupt power failures and system crashes. Last but not least, it also stores data in compressed form. Multiple compressing schemes are available, according to whether matters more: read/write performance or the compression rate. For example, zlib compresses better than lzo, but is also much slower.

Wear leveling (also written as wear levelling) is a technique for prolonging the service life of some kinds of erasable computer storage media, such as flash memory, which is used in solid-state drives (SSDs) and USB flash drives, and phase-change memory.

Implementing flash filesystems has special constraints. When you make a change to a particular file, you shouldn’t just go the easy way and copy the corresponding blocks to RAM, erase them, and flash the blocks with the new version. The first reason is that a power failure during the erase or write operations would cause irrecoverable data loss. The second reason is that you could quickly wear out specific blocks by making multiple updates to the same file. The solution is to copy the new data to a new block, and replace references to the old block by references to the new block. However, this implies another write on the filesystem, causing more references to be modified until the root reference is reached.

JFFS2 uses a log-structured approach to address this problem. Each file is described through a “node”, describing file metadata and data, and each node has an associated version number. Instead of making in-place changes, the idea is to write a more recent version of the node elsewhere in an erase block with free space. While this simplifies write operations, this complicates read ones, as reading a file requires to find the most recent node for this file.

Back to node management, older nodes must be reclaimed at some point, to keep space free for newer writes. A node is created as “valid” and is considered as “obsolete” when a newer version is created. JFFS2 managed three types of flash blocks:

- Clean blocks: containing only valid nodes

- Dirty blocks: containing at least one obsolete node

- Free blocks: not containing any node yet

JFFS2 runs a garbage collector in the background that recycles dirty blocks into free blocks. It does this by collecting all the valid nodes in a dirty block, and copying them to a clean block (with space left) or to a free block. The old dirty block is then erased and marked as free. To make all the erase blocks participate to wear leveling, the garbage collector occasionally consumes clean blocks too.

https://sourceware.org/jffs2/jffs2-html/node3.html

To optimize performance, JFFS2 keeps an in-memory map of the most recent nodes for each file. However, this requires to scan all the nodes at mount time, to reconstitute this map. This is very expensive, as JFFS2’s mount time is proportional to the number of nodes. Embedded systems using JFFS2 on big flash partitions incurred big boot time penalties because of this. Fortunately, a CONFIG_JFFS2_SUMMARY kernel option was added, allowing to store this map on the flash device itself and dramatically reduce mount time. Be careful, this option is not turned on by default.

There are two ways of using JFFS2 on a flash partition.

The first way is to erase the partition and format it for JFFS2, and then mount it. Note that flash_eraseall -j both erases the flash partition and formats it for JFFS2. You can then fill the partition by writing data into it.

flash_eraseall -j /dev/mtd2

mount -t jffs2 /dev/mtdblock2 /mnt/flashThe second way, which is more convenient to program production devices, is to prepare a JFFS2 image on a development workstation, and flash this image into the partition:

flash_eraseall /dev/mtd2

nandwrite -p /dev/mtd2 rootfs.jffs2To prepare the JFFS2 image, you need to use the mkfs.jffs2 command supplied by mtd-utils. Do not be confused by its name: unlike some other mkfs commands, it doesn’t create a filesystem, but a filesystem image. You first need to find the erase block size (as explained earlier). Let us assume it is 256 MiB. Then create the image on your workstation:

mkfs.jffs2 --pad --no-cleanmarkers --eraseblock=256 -d rootfs/ -o rootfs.jffs2-d specifies is a directory with the filesystem contents --pad allows to create an image which size is a multiple of the erase block size. --no-cleanmarkers should only be used for NAND flash.

YAFFS2 is Yet Another Flash Filesystem which apparently was created as an alternative to JFFS2. It doesn’t use compression, but features a much faster mount time, as well as better read and write performance than JFFS2. YAFFS2 less popular than JFFS2, and this is probably because it is not part of the mainline Linux kernel. Instead, it is available as separate code with scripts to patch most versions of the Linux kernel source.

To use YAFFS2 after patching your kernel, you just need to erase your partition:

flash_eraseall /dev/mtd2The filesystem is automatically formatted at the first mount:

mount -t yaffs2 /dev/mtdblock2 /mnt/flashIt is also possible to create YAFFS2 filesystem images with the mkyaffs tool, from yaffs-utils.

JFFS2 and YAFFS2 had a major issue: wear leveling was implemented by the filesystems themselves, implying that wear leveling was only local to individual partitions. In many systems, there are read-only partitions, or at least partitions that are very rarely updated, such as programs and libraries, as opposed to other read-write data areas which get most writes. These “hot” partitions take the risk of wearing out earlier than if all the flash sections participated in wear leveling. This is exactly what the Unsorted Block Images (UBI) project offers.

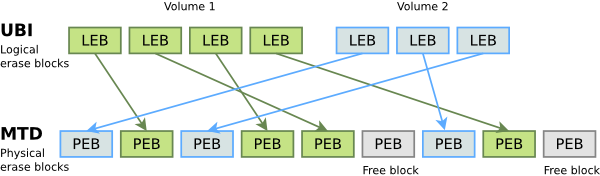

UBI is a layer on top of MTD which takes care of managing erase blocks, implementing wear leveling and bad block management on the whole device. This way, upper layers no longer have to take care of these tasks by themselves. UBI also supports flexible partitions or volumes, which can be created and resized dynamically, in a way that is similar to the Logical Volume Manager for block devices.

UBI works by implementing “Logical Erase Blocks” (LEBs), mapping to “ Physical Erase Blocks” (PEBs). The upper layers only see LEBs. If an LEB gets written to too often, UBI can decide to swap pointers, to replace the “hot” PEB by a “cold” one. This mechanism requires a few free PEBs to work efficiently, and this overhead makes UBI less appropriate for small devices with just a few MB of space.

UBIFS is a filesystem for UBI. It was created by the Linux MTD project as JFFS2’s successor. It also supports compression and has much better mount, read and write performance.

Managing flash storage with Linux

Flash (SSD) Technology (And Beyond) Fundamentals — So-Cal Engineer