Inspired by this numberphile video, this project was one of my first strange excursions into functional programming.

The aim of the game was to iterate through 3-space as efficiently as possible trying to find the solution to this equation:

A simple proof clearly shows that all numbers of the form 9n±(4,5) have no such solution:

The residue of a positive number modulo n is whatever is left after removing n from it until the new number is between 0 and n - 1 inclusive.

Further modular arithmetic is simply adding, subtracting numbers between 0 and n-1, and then removing n until it falls under the range.

For example:

And 12 mod 9 is represented best by 3 mod 9. (An example of a member in the same equivalence class that is negative is -6 mod 9. Add 9 to -6 to get our representative.)

Every integer, when cubed, has a residue of 1, 0, or 8 modulo 9 (the proof of this isn't hard once you know the trick, but I'm taking it for granted here). So adding three numbers can never get you a residue of 4 or 5. The residue of any number of the form 9n±(4,5) is in fact 4 or 5.

So we know for a fact there is no integer solution to 4, 5, 13, 14, 22, 23.. as these are all of the form we just stated.

But 33 isn't of that form. No one has found a proof either way concerning the existence of a solution for 33.

This code was an attempt to find that solution, until I got a first hand account of how algorithms like the one encoded here scale: traversing R^3 is terribly unexciting after the first cube of 10,000.

Initially me and my complex analysis professor stripped out lots of values pertaining to the parity (only two or none may be even, for example). But asking my graph theory professor uncovered something rather pertinent, that you can eliminate most trials by realizing any integer cubed mod 33 has the same residue as everything in its equivalence class (which I guess is obvious when you say it that way, but I do recall spending some time proving it). That's not the case for all numbers, and it clearly isn't the case for prime moduli, as modular arithmetic tends to like. That prompted code in ./side looking for smooth residue profiles (probably the strangest name I've written for a function yet).

Anyway, while I found exploration of that aspect interesting, (there is a smooth-residue-profile of all equivalence reps raised to the third, raised to the ninth, and generally, raised to the 3^n mod 33) it still wasn't a linear time algorithm. The mathematician in the video had checked everything under 10^14. Either there is a linear time algorithm or he has one sick compute cluster. I could not get anywhere close to that on a single Debian VPS.

But of course writing this taught me a lot. After a while, I wanted to watch my algorithm in action, and I wrote in some non-blocking code (when I really should've been looking for a concurrency module) to check for activity in stdin. That way I could monitor progress. I remember being giddy showing my math professor how fast it threw out numbers to stdout.

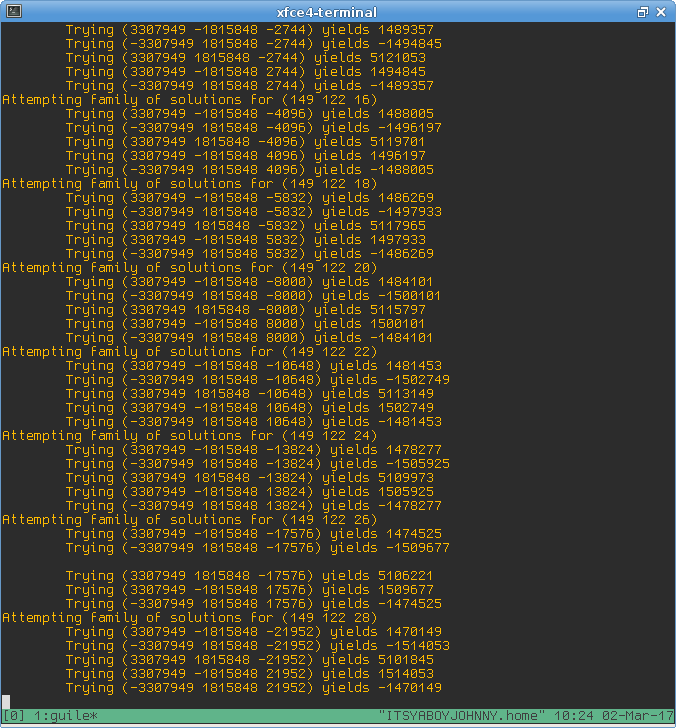

guile -l main.scm (Provided you've cloned the repo, and have guile installed). Inputting 'v' and hitting enter causes verbose output to occur, where every try and the results are logged to stdout

Here is an example of what verbose output looks like:

To end verbose output, use "c", and hit enter. It will instead display a final computation, and resume intended functionality converting your computer to a very inefficient space heater.

There isn't a way to serialize state, that was planned but never implemented. Instead, you can feed input to it just as you would on the command line. Main will sanitize the inputs to make sure they are right (the 'rules' are in sanitize.scm, requiring pivot to be even, some parity checks, etc), and if not, exit. Otherwise it'll chug along at what you feed it.

It's not likely.

As I was going through SICP at the time, I was (and still am) enamored with tail call optimization. Everything in here tries to embody that, even the interface is tail call optimized, in that every call to display something also carries state with it, which is eventually passed back to silent, traditional computing.

If I were to rewrite this, I would absolutely do it in Racket, specifically because their docs on concurrency are very clear over Guile's. I don't intend to use concurrency for speed or threading, instead I would use it to provide a clear interface to the program state.

In order to 'see' it, though, I'd have to deposit the last set of trials in some shared state, which as far as I can tell can't be done functionally, or definitely not the way I did it here. Perhaps I'd even do it in Python, instead.

However there really is no reason to write this over if I do not have a linear time algo. I think about it from time to time, and sometimes I fill a page with thoughts and hopes, but so far I haven't cracked it. Maybe someday :)

Traversing 3-space is kinda like using Cantor's pairing function, except I couldn't find an easy way to map the integers to traversal. More on this at the end.

The algorithm uses exclusively 3 tuples, where each element is lesser than the previous. This removes the possibility that we hit the same equation twice, that is: 5^3 + 3^3 + 2^3 is the same as 3^3 + 5^3 + 2^3, so there is no sense in checking both. We call these 3 tuples pivot lists. The function increment-3-pivot-list takes in a pivot list, and returns the next one in such a way that every possible pivot list is returned exactly once.

A pivot list never has 0 as its elements, as there is no 2 dimensional solution to the equation we're interested in.

We are always guaranteed one or three odd number(s) in the solution, so the pivot is the one that is always odd. This makes incrementing much easier, as we can then iterate through all the solutions with two even non-pivots, and two odd non-pivots.

We abstract away the signs so that we're only responsible for the space where all numbers are positive. We map a pivot list to its cubes, then map it to a bunch of sign configurations. IE:

> (list-generate (5 3 1)

$1 = ((125 -27 -1) (-125 27 -1) (125 27 -1) (125 -27 1) (-125 27 1))This allows us to break up our pivot lists into different types and draw reasonable conclusions about them, allowing us to save some computation when we identify them:

For all possible pivot lists:

- there are no solutions of all negative and all positive signs.

For ones that are all distinct: (5 3 1)

- Since we know the pivot is >= the rest of the list, we don't need to map to (-1 -1 1), since that would be a negative value.

For ones that have their 1st and 2nd as duplicates: (5 5 3)

- There is no way that the signs of the first two differ when cubed, as they'd cancel each other out, giving us the integer cube root of 33, which doesn't exist.

For ones that have their 2nd and 3rd as duplicates: (5 1 1)

- Analogous to the above, except signs of the last two cannot differ here.

For ones that are triplets, where all are the same value

- They're never a solution :(

Alluded to before, if you cube the equivalence representatives of mod 33, they all map to different values.

guile -l side/modulo.scm> (prettyprint 3 33) ; exponent, modulus

(32 32)

(31 25)

(30 6)

(29 2)

(28 7)

(27 15)

(26 20)

(25 16)

(24 30)

(23 23)

(22 22)

(21 21)

(20 14)

(19 28)

(18 24)

(17 29)

(16 4)

(15 9)

(14 5)

(13 19)

(12 12)

(11 11)

(10 10)

(9 3)

(8 17)

(7 13)

(6 18)

(5 26)

(4 31)

(3 27)

(2 8)

(1 1)

(0 0)Note the bijection, again, as mentioned before.

Then you enumerate all the weak 3-decompositions of 33 (I took the liberty of solving this in python, for all integers). These are the residues you are looking for. Perform a reverse map, and if there is a solution, it has to be of one of these forms. The additional optimizations above can also be considered, although they sadly do not a linear algorithm make.

Enumeration through these are simple. Save the decompositions as a map, and enumerate through 3-space (any isomorphism between R and R^2 works here), subject it to the same restrictions as above and you've got a much more efficient search, albeit still growing in O(N^3) time.

Yet another approach is the heuristic one. Given any attempt, adding or subtracting 1 from any of the numbers affects the sum specifically. An attempt to only choose increments that approached 33 or minimized deviation from it would be a linear search (and such a search would be deterministic given a constant min deviation function). This is slightly more complicated, but for example:

Say you have 5^3 + 5^3 - 6^3 = 34. Adding 1 to either of the 5s jumps from 1 off the solution to 91 off. But subtracting 1 from the 5s yields a solution that is only 60 off (although negative). So subtract 1, and repeat, keeping track of previous tries.