Building a machine learning model around Pokemon card prices and rarity

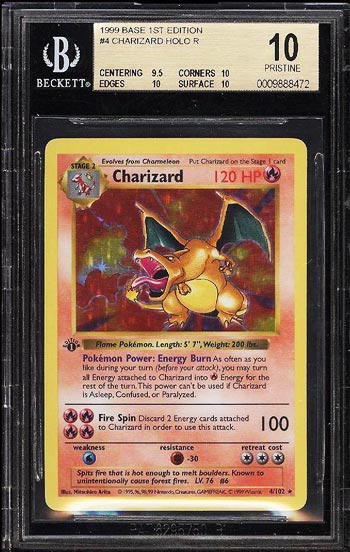

The Pokemon card market has experienced a dramatic surge in popularity, especially following the COVID-19 pandemic. What started as a children’s trading card game has transformed into a high-stakes collectors’ market, where rare and legendary cards can sell for hundreds of thousands of dollars. The rise of professional grading companies, which certify card quality and condition, has further fueled the demand, creating a competitive marketplace with unprecedented prices.

This topic was chosen because of the group’s shared passion for Pokemon and the need for reliable, data-driven tools in this rapidly growing, multi-million-dollar industry. Pokemon universally appeals to generations of people, making this an exciting and relatable subject, as even enthusiasts like Professor Solares would agree (we think). While traditional methods—such as relying on anecdotal evidence, historical data, or recent transactions of a similar card and quality—can provide some guidance, they often result in inefficiencies and inaccuracies, leading to undervalued or overpriced cards. As the market continues to expand, a more sophisticated and structured approach to evaluating card rarity and market value is essential.

To address this need, this study incorporates several advanced machine learning techniques to predict the rarity of Pokemon cards based on features such as grade quality, statistics (i.e. Health Points, Evolution state, Move Damage), and visual features (i.e. regular, holographic, reverse holographic). Predictive models include random forest classifiers and neural networks, designed to identify relationships between card characteristics, rarity, and pricing trends. This study also explores broader market trends from 2021 onward, using methods like linear regression and neural networks to identify key factors influencing Pokemon card prices.

This topic is particularly cool because it combines a popular hobby and machine learning techniques. Pokemon card collecting has evolved into a sophisticated and lucrative global market, and by enabling accurate predictions of card rarity and value, this research enhances the collecting experience while promoting fair pricing and informed decision-making. Data-driven predictions have the potential to stabilize and bring more transparency to the Pokemon card marketplace. The broader impacts of this research extend beyond the Pokemon card market, providing a foundation for improving valuation in other collectible industries. By replacing reliance on anecdotal evidence and word-of-mouth pricing with machine learning models, this study ensures greater transparency and efficiency in high-value markets. As these models evolve, they may soon become integral to future pricing techniques, influencing buyers and sellers with reliable data to make informed decisions. This approach ensures market stability and promotes a sustainable, equitable framework for collectibles industries worldwide.

Our data was collected by combining two datasets. One was scraped by using a price charting API. The other dataset was pulled from a Kaggle Pokemon dataset. One problem we encountered was a disparity in ID systems between the two datasets. After some analysis of the ID names and their set names, it seemed like most of the datasets had a conversion by using their set name combined with an en dash(“-”) and their card number within the set. A few sets had to be ignored due to inconsistent naming. Although before we had around 50,000 observations, after combining datasets we had a total of 30300 observations with 56 features. This combination process was documented and is repeatable with the scripts in the repository.

After collecting our data, we becan exploring trends in it to inform our hypotheses better for the models to follow. For instance, the figure below shows the average graded price of Pokémon cards by type (left) and rarity (right). Notice how "Colorless" cards have the highest average graded price among types, while "Rare Holo" cards are significantly more valuable compared to other rarity categories!

For our categorical data, we used value_counts() to quickly comb through columns of our chosen features to pick out which categories would be difficult to map due to the extremely low population. For example, all of the dual-typed cards were dropped due to very low counts compared to the rest of the types. After looking through rarity, types, and generation and their value counts, the feature counts containing less than the following were dropped. Then the input feature categorical variables were one hot encoded.

thresholds = {

'types': 1000 ,

'rarity': 1000 ,

'generation': 1500

}

for col, threshold in thresholds.items():

counts = subset_df[col].value_counts()

valid_categories = counts[counts >= threshold].index

subset_df = subset_df[subset_df[col].isin(valid_categories)]

One Hot encoding

encoded_df = pd.get_dummies(subset_df, columns=['types', 'generation'], drop_first=True)

Note that for model 2, the numerical features were standardized:

encoder = OneHotEncoder()

types_encoded = encoder.fit_transform(subset_df[['types']]).toarray()

generation_encoded = encoder.fit_transform(subset_df[['generation']]).toarray()

numerical_features = ['bgs-10-price', 'graded-price', 'hp', 'sales-volume']

scaler = StandardScaler()

numerical_data = scaler.fit_transform(subset_df[numerical_features])

final_features = np.hstack([types_encoded, generation_encoded, numerical_data])

In addition, we created the following correlation heatmap to analyze the relationships between key features in our dataset, such as card prices, sales volume, and health points (HP). The plot helps us identify strongly correlated variables, such as the high interdependence between different pricing metrics (e.g., loose-price, graded-price, box-only-price). Conversely, it reveals weak correlations, such as between sales volume, suggesting these may have less predictive power for card valuation or rarity. This analysis informs our feature selection process by highlighting which variables are most meaningful for our models and which may need further investigation or exclusion. Ultimately, the heatmap provides critical insights for optimizing the performance and efficiency of our machine learning models.

Further preprocessing was required during tuning and reevaluation of our model 1 as well. After analyzing our pair plots, we attempted to drop some detail in our data as well as our output classes to make achieving a higher accuracy more plausible. We noticed that extremely high costs of a few cards were seen in our pairplots, causing the x-axes to stretch further than the others, which led us to believe high-cost cards were throwing our models off. Therefore we decided to drop the top 1% quartile of prices.

The following is what our pair plot looked like without removing the outliers:

As for dropping detail, after coloring pair plots by rarity, it became evident that many of the previous 4 different rarity classes were overlapping in qualities, so much so that it would just be more useful to merge a few of the classes. This overlap is likely due to the idea that generally cards seem to be in a more binary category for either rare, being very high price (cards worth more than around a dollar) or lower price (only worth cents). Since rarity is categorical but still ordered, we were able to group common, uncommon, rare, and rare holos into common combined with uncommon and rare combined with rare holos. This is not unexpected due to the idea that rare holo and holo are essentially the same cards statistically, other than an added shiny visual effect.

Furthermore, we explored how features like pricing and conditions related across card collections and informed the model-building process, and choosing our input/output variables. The figure below visualized the pairwise relationships between numerical features in the dataset, categorized by the top three most common Pokémon card sets: Pokémon Promo, Silver Tempest, and Unbroken Bonds. Each point in the scatter plots represented a card, and the colors differentiated cards from these three sets. The diagonal tells us te variability within a set.

Merging output classes and dropping outliers

top1 = subset_df['graded-price'].quantile(0.99)

subset_df = subset_df[subset_df['graded-price'] < top1]

subset_df['rarity'] = subset_df['rarity'].replace('Common', "Common/Uncommon")

subset_df['rarity'] = subset_df['rarity'].replace('Uncommon', "Common/Uncommon")

subset_df['rarity'] = subset_df['rarity'].replace('Rare', "Rare/Rare Holo")

subset_df['rarity'] = subset_df['rarity'].replace('Rare Holo', "Rare/Rare Holo")

Dropping Null values for the last time

subset_df = subset_df.dropna()

- Split the data into 5 folds for training and validation.

- We train and evaluate model on different subsets of the data to prevent overfitting

- Following are the training accuracies for each fold:

[0.77840344 0.77475985 0.76507621 0.75878065 0.77269715]

The trend in the training accuracy across folds can be seen below:

The first model used random forest as an expedition into tree based algorithms as this was chosen before deciding to merge classes. After observing patterns in our data for some time, the non-linear, complex patterns that were difficult to pin down seemed like a good candidate for random forest classification. There were a few problems that came from this model initially, like accuracy, however biggest factor was the high overfitting indicated by 100% training set accuracy compared to a validation and test accuracy in the 60s. Due to time limitations, the model was not fully fixed until a later milestone, which addressed much of the overfitting problems, tuned hyperparameters and merged classes for increased accuracy. At the same time, we found that increasing n_estimators up from a default of 100, to 220 allowed us to increase accuracy while keeping our training accuracy close to testing and cross validation accuracy.

Tuning manually, we found most of the default parameters for the RandomForestClassifier to be optimized. Of the hyperparameters changed, the most impactful for reducing overfitting was decreasing max_depth to 10. The default max_depth is set to 30, and decreasing it forces our forest to capture less details per tree in our data allowing for higher generalization in our model. With a few iterations, we found that reducing it past 10 began to seriously become detrimental to the accuracy of our model, so 10 was set as our optimal hyperparameter. min_samples_split was also slightly changed to a default of 2 to 4 for a very minimal boost in accuracy. ccp_alpha, max features and min_samples_leaf made little difference or negative impact to change so we left them at their default values and finished our tuning.

Tuning results can be seen below as text file outputs using loops as this was done before learning of search tuning. https://github.com/charvishukla/cse151a-pokemon-project/tree/Milestone4/reduce-overfit-tuning

For our second model we decided on a Neural Network to predict the rarity of Pokemon cards based on both categorical and numerical features. We used One Hot encoding to encode our categorical data as well as Standardized our numerical data to prevent any feature from dominating during learning. After processing the data we ended with 21 features and 12631 rows. For our hyperparameters we used binary cross-entropy loss due to our target feature, rarity, being able to be represented in binary format. Some of the hyperparameters that we tuned were the learning rate, ultimately decided on 0.001 and our optimization method, ending with Stochastic Gradient Descent.

Due to the fact that we had some issues with overfitting with the last model, for this model we applied a dropout on 30% of the working neurons to prevent the network from over-specializing on specific neurons, this process is found in this line: self.dropout1 = nn.Dropout(0.3). Finally, we trained our model for 1000 epochs to make it converge as seen with the Training and Testing Accuracy Graphs

Initially, the model exhibited overfitting, with 100% training accuracy but only 67% testing accuracy. This large gap indicated that the model was memorizing the training data instead of generalizing well to unseen data.

To address this:

The number of trees n_estimators was increased to 220.

The maximum depth of the trees max_depth was limited to 10.

The minimum samples required to split a node min_samples_split was set to 4.

These changes encouraged the model to better generalize to unseen data by limiting its complexity and avoiding overfitting patterns in the training model. As a result: Training Accuracy was reduced to 0.895, closer to the testing accuracy. Testing Accuracy improved to 0.841, indicating better generalization.

The following classification report summarizes the performance of Model 1.

- Accuracy (0.84): The model correctly predicts the rarity of Pokémon cards 84% of the time. The performance is slightly better for the

Common/Uncommonclass (precision, recall and F1 score of 0.87) compared to theRare/Rare Holoclass (precision, recall and F1 score of 0.80) - Macro Average: Precision, Recall, F1-Score (0.83). This indicates that the model treats both classes fairly equally.

- Weighted Average: Precision, Recall, F1-Score (0.84). This shows that there is consistency with the overall dataset distribution.

Here is the terminal output for the classification report:

precision recall f1-score support

Common/Uncommon 0.87 0.86 0.87 1510

Rare/Rare Holo 0.80 0.80 0.80 1018

accuracy 0.84 2528

macro avg 0.83 0.83 0.83 2528

weighted avg 0.84 0.84 0.84 2528

The following is our learning curve (after preventing and adjusting for overfitting):

We see the trajectory of the neural net's training accuracy over epochs to be over 80%, settling at around 84% which is near the testing accuracy of also around 84%. This gives an indication that overfitting is not a large problem at play for our model.

At the beginning of training, the loss is initially very high, but begins to sharply decrease for around ~50 epochs. Past this, for 100 epochs, a transition to a plateauing shape can be observed which can be interpreted as a sort of "fitting". Furthermore, the longer the training goes, we do not see an increase in loss besides noise, rather, a slow decline. This indicates that the model is fitting the data rather than overfitting which may be indicated by an increasing loss after fitting.

The following are our diagrams for training accuracy and training loss:

Compared to the previous model, the main differential is the difficulty in fitting. To reduce the overfitting problem from before required tuning the number of trees in our forest in n_estimators as well as artificially limiting the depth of our trees with max_depth to better capture generality rather than capture specific patterns in our training data. Other hyperparameters were tested but were found to decrease overall accuracy.

The neural net does a similar adjustment process automatically for weights during training, which made the fitting more natural for the model and required comparatively little manual adjustment on parameters. Here are the results from our confusion matrix:

Correct Predictions (Accuracy): 3177 False Positives (FP): 270 False Negatives (FN): 343

To initially begin finding a dataset, there were a few goals in mind. Something large enough to be optimal for a neural network, a dataset involving images, and data containing many features. We arrived at a few options but fell short of an ideal dataset based on these goals. To remedy this, we combined two datasets and scraped another image dataset that eventually went unused due to time constraints on milestone 5.

In milestone 2, most of our time was spent on data scraping and data processing; The dataset was riddled with pockets of zeroed prices and missing features which led our initial dataset of 60,000 to be reduced to 17,000. This cutdown was unfortunate but required as it would be difficult to interpret prices. Additionally, during this milestone, we began to label our features which required some background knowledge of Pokemon cards to understand. Here we tried to identify patterns visually in our pair plots and tested a few simple regression models. Despite the feature transformations we attempted, there was still a large spread in the pair plots which made sense as to why simpler models could not pick up on the patterns. The pair plots revealed weak 2-dimensional trends that were highly expected like the fact that there was a general increasing trend for many features, but a fair amount of outliers caused the pairplot graphs to stretch further than they should. This gave us ideas for transforming our features and to weed out a percentile of outliers.

Therefore, after much pruning, feature correlation reasoning, and pair plot spread interpretation we decided on our target outcome feature to be card rarity, while the features we used to predict were card type, generation, best-graded condition price, general graded price, health points, and sales volume of the card. For type, it looked like certain types were associated with higher prices, and as a proxy, rarity because prices are consistently related to rarity. From this information it might seem like rarity and price should be directly correlated factors, however analyzing their pairplot and background knowledge about the Pokemon card market reveals that there are many other factors at play. Pokemon cards’ prices do have a high correlation with their rarity but are often brought to extremes through their age, visual elements like art satisfaction, and playability in games. Thus, we attempted to capture these elements through card generation for age, and health points for playability. Additionally, higher prices imply scarcity which is indicated by our sales volume feature.

For milestone 3, we approached the dataset with a few simple models to test for initial compatibility, however, many of these models led to lower-than-expected accuracies. This somewhat random spread of rarities gave the inspiration to apply the random forest classifier. This model did have much higher accuracies than the others tested, however it was still quite low, being sub 70%. This was unsatisfactory to our group, and the short-term conclusions we drew from this model were that since we had 4 output classes the high overlap in feature similarities threw off our accuracy, and not hyperparameter tuning was causing extreme overfitting. This was later remedied in a later milestone, and with decent results, bringing our accuracy up almost 20% and essentially reducing most of the overfitting which was evident in our training accuracy compared to previous.

Milestone 4 was a more involved milestone in that the neural net was implemented using PyTorch (instead of Tensorflow) and required more self-tuning and a from-scratch implementation. While training the model itself took the longest and the accuracies were very similar, we feel that this model had the best “learning” compared to the previous model. This interpretation comes from the fact that model 2 has a much closer training and testing accuracy as well as an identifiable loss curve with a significant decrease at first and a consistent downward slope, indicating that the training converged steadily. The best loss function was clearly binary cross-entropy, a common loss function for binary classification. A few static parameters we decided on to keep training time lower were stochastic gradient descent with a learning rate of 0.001. The hyperparameters adjusted for our neural network were dropout rate, epoch count, and activation function. The dropout rate was manually tuned to reduce overfitting, while the epoch count was chosen based on the loss curve and cut off when the learning began to stagnate or increase overall loss. Finally, the sigmoid function was found to be optimal in this application due to the binary classification that we had decided as our output variables.

We had hoped for our model to have been far more accurate given the amount of data we had and with more time, it would have been much more interesting to try and implement our classifier with the image data we scraped (~17k unique images). This is especially due to a hypothesis we had about image geometries and color and their relation to rarity and price. A few regrets were failures to recognize complex patterns in data, and low correlation in pairplots early, which led to confusion and frustration during our initial model exploration. Furthermore, using gridsearch, and other tuning search methods would have made our tuning much less taxing on our time spent on tuning the models.

In the beginning, we started with a dataset containing about 30300 observations and 56. This dataset resulted from merging two separate datasets, of which one was scraped using an API. Throughout this project, we were only able to utilize a small subset of this dataset’s features as many features proved irrelevant after processing. We built a Random Forest and a simple Neural Network to predict the rarity of a Pokemon Card, based on a combination of categorical and numerical variables. The results from our Random Forest and Neural Network was as follows:

The models of our choice — although powerful and simple — were only able to handle a small subset of our features, given the amount of data. Thus, in the future, to tackle such complexity, we aim to work with Ensemble Models. These models would employ a combination of Machine Learning algorithms instead of just one, leading to greater predictive power and generalizability.

There are many different possible routes we wanted our project to extend to. We realized in the time that we were allotted for this project that we would only be able to predict Pokemon Card rarity based on our selected features. In the future, we would like to create models that can accomplish other tasks within the Pokemon Card market space. This includes models that could predict the price of a card or the possible grade a card may receive based on a provided image of said card. We also worked a lot with models focused on classification for this project. Though classification was productive in our case, there is a case that can be made that choosing a different model for finance related data could help improve our accuracies further. However, we were able to build a high accuracy model with classification for the task we aimed for.

We are definitely not the first group of people to ever build a functional machine learning model to predict characteristics of a Pokemon Card. Many researchers and students have created successful models that accurately predict factors such as price and rarity. In fact, research has shown that there are some models that are more accurate at grading cards than trained professionals hired at grading companies. Despite this, the adoption of machine learning in the Pokemon Card market is still something that is heavily debated. Sellers and buyers in the market prefer the opinion of authorized graders over machine learning models that are created by researchers. Even if the grading of a card is more subjective overall with a human due to bias, many individuals still choose to accept the opinion of the elite rather than algorithms trained with statistical data. As a result, machine learning may need more of an introduction to the community as a tool for our benefit. As models become more accurate and further research is done on Pokemon Cards, we believe the legitimacy of machine learning in the market will be extremely beneficial. Therefore, the research we have done serves a purpose greater than just obtaining a grade for the class. It provides a means of objectivity in a market where everyone is trying to prove the worth of their own Pokemon Card collections.

Charvi Shukla: Team member/programmer/analyst: Worked on implementing the neural network, and its corresponding graphs. Collaborated with team mates on the exploratory data analysis section.

Pedro Arias: Team Member/writer: Collaborated on methods section for final writeup, communicated with group, aided in milestone writeups and ensured all questions were answered.

David Kim: Team member/programmer/writer: data gathering and merging scripts with background knowledge in pokemon cards. Tuned hyperparemeters for model 1 and provided supporting analysis on results for model 1 and 2. Wrote the discussion section and collaborated on writing the methods section.

Kenneth Song: Team member/writer/coordinator: Introduction writeup portion, organized writeup figures to use, set up meetings, double checked work before submissions, communicated often with group

George Li: Team member/writer/researcher: Suggested and researched the pokemon dataset, brought background information about topic, worked on conclusion section for final writeup, collaborated on various milestone writeups, communicated often in group

Anthony Georgis: Team member/writer/analyst: Results writeup portion, helped with classification reports and metrics used and double checked work before submissions.